The Schizophrenic Personality | Understanding Schizotypal & Schizotypy

Before we had schizotypal personality disorder in the DSM-III in 1980, we had a bunch of different people investigating a schizophrenia-like personality involving names such as: “latent schizophrenia,” “schizoid personality or character,” “schizoform abnormalities,” “borderline schizophrenia,” “ambulatory schizophrenia,” the “as-if personality,” and “pseudoneurotic schizophrenia.”1 2 These terms were coined because clinicians discovered individuals who didn’t actually develop schizophrenia, but who were also more severe than schizoid personalities. This area in-between was eventually called schizotypy1 3 4. Schizotypy traits have been researched from a genetic standpoint, research, and from clinical experience. Meehl’s model was, and still is, the most influential and comprehensive research on this topic, and current studies are still confirming his original proposals1 3 4. Let’s look deeper into his thoughts!

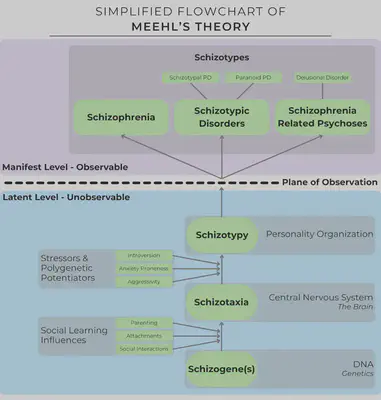

Meehl’s Integrative Model of Schizotypy1 3 4

Meehl’s model of schizotypy is comprehensive, and thus quite nuanced and difficult to understand, so please check out his actual papers for more information (1962, 1990). Here, I’m going to simplify his concepts and use the creation of a wooden cabin to help us understand the creation of a person who has schizotypy.

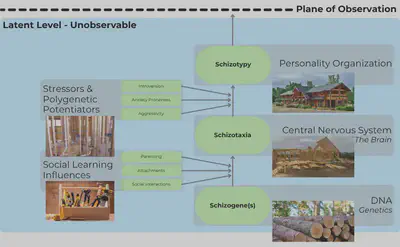

🪵 The Materials: 🧬 DNA and the Schizogene

When building a house, you must start with materials such as wood, nails, and electric components. In the same way, infants start with DNA and genetic material. Meehl identified that there is a DNA-based genetic liability for schizophrenia, which he called the schizogene (but it’s more than just one gene)1. This is where the house and the schizotype starts.

🖼️ The Frame: 🧠 Schizotaxia and the CNS

From the materials, we start to build a frame. For the house, this is structuring the shape and functionality of the cabin, and for the schizotype, it’s structuring the central nervous system (CNS) with the brain and neural circuitry. Here is where we see the potential for some problems that are unique to schizotypy. The schizotype has impaired neural circuitry - called schizotaxia - that involves a potential for cognitive slippage that can later lead to loose thinking. Now, the equivalent in the cabin analogy would be if the electrical circuit’s switches had problems controlling where the energy goes. That can lead to increased potential for short circuiting or odd electrical jumps, like if you turn on the kitchen light switch, the bathroom fan turns on instead.

🛠️ The Tools: 👥 Social Learning Influences

In the process of building, you need some tools, which are acquired through life’s influences. Do you have access to your father’s power tools? An excavator shared by a community? Or just a hammer and handsaw that you had to pick up on your own? The tools are the equivalent to social learning influences involved in parent-child dynamics, attachments, and other early social interactions. If your parent helped you develop more positive self-esteem, you have a “better” tool than a different person who had a parent that tore them down and didn’t give them a tool to use.

🏠 The House: 🤔 Schizotypy as a Personality Organization

We started with materials (DNA, genetics) and framed the cabin (CNS, schizotaxia) with tools (social learning influences). So now, we can add walls and a roof and all those things that make a cabin, but it gets a bit tricky. There’s no way to escape the personality organization of schizotypy at this point. We can’t create a skyscraper with logs and a handsaw; we are set in building a cabin. However, a person with more materials and better tools might be able to make a more functional cabin (aka non-disordered schizotypy), but it’s still going to be a cabin.

→ 🛋️The Interior Design: 🥺Stressors and Polygenetic Potentiators We can’t forget about the interior of the cabin! Does it have brightly painted walls, a couch in the dining room, or throw pillows on the kitchen counter? The internal functionality and decor of any structure is vastly individualistic. In Meehl’s model, he calls the internal individualist influences “stressors and polygenetic potentiators.”3 4 Big words, right? But really, he’s just talking about things like trauma, introversion, anxiety proneness, anhedonia, aggressivity/dominance, etc. Every schizotype is going to have an individualized design… and for some schizotypes, their oddness may never be seen by anyone other than themself (aka non-disordered schizotypy). It’s possible this is where schizoid personalities veer off.

Anyway, everything we discussed above the plane of observation here is at the “latent” level where we cannot see it. Just like, you can’t drive by a house and see its electrical wiring or kitchen table, you can’t just see a schizotype’s neural structure or trauma - unless invited in.

| - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 🛩️The Plane of Observation🛩️- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - |

|---|

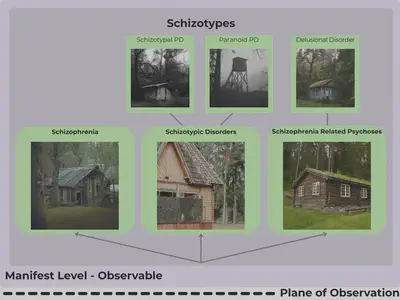

🙋 The Zillow Profiles: 👀 Manifest Level of Observable Schizotypes

Everything we’re going to discuss now is at the “manifest” level, which is observable - kind of like Zillow profiles. The cabins are all unique and different and can present in a variety of ways, just like schizotypes can. → Schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia is the persistent psychotic presentation of schizotypy. The cabin might look like it’s falling apart or be completely disorganized with a toilet next to the refrigerator.

→ Schizophrenia Related Psychoses

- Schizophrenia related psychoses include presentations of short term or intermittent psychosis like delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and schizophreniform disorder. These cabins may be painted like a red and orange butterfly, then like a neon green spaceship 6 months later. There’s a lot of variety here!

→ Schizotypic disorders

- Schizotypic disorders include schizotypal personality disorder and paranoid personality disorder, in which both can experience borderline psychosis. A schizotypal cabin might be hidden in a bunker-link manner due to fear of others, and when you walk in it, it may be chaotic and bizarre. A paranoid cabin may be hidden in a tree with 53 locks and an intense surveillance and weapon system.

What is Schizotypal Personality Disorder

(as a schizophrenic/schizotypic personality)

Per Meehl’s research1 3 4, he identified four fundamental signs and symptoms of schizotypy, which mostly aligns with how the DSM conceptualizes schizotypal personality disorder5, but it goes deeper. He noted cognitive slippage (mild associative loosening, on the verge of psychosis), interpersonal aversiveness (social fear), and ambivalence (contradictory attitudes/emotions) to be foundational to a schizotypal personality. Early in his research, he also believed anhedonia to be imperative3, but later deemphasized this, believing it may simply be an additional genetic trait that may or may not be present in schizotypy4. But what does this actually look like? The foundational signs and symptoms are expressed physically, cognitively, emotionally, and socially.

💪 Physical

Those with schizotypal personalities may have an unkempt appearance with ill fitting clothes, as they can have low weight and odd/bizarre fashion5 1. They can also have proprioceptive difficulties, meaning they might misjudge the length of their limbs5, have a skewed perception of their physical self in space, or even feel like their body isn’t solely in their control. Sometimes, they might move in odd ways to remind themselves they are alive, obtaining deep pressure input to ground themselves in awareness that they are human1 2 6.

🧠 Cognitive

Their reality testing is on the fringe of psychosis, making it “borderline”… like literally bordering the line of psychosis. They are at risk for “cognitive slippage” (schizotaxia), odd perceptions, decreased attention, under/overactive senses, impaired eye tracking/contact, magical thinking, and ideas of reference5 1 2 6. They can experience paranoid ideation, consistently wondering who is out to get them, which plays into their social anxiety5 6.

😭 Emotions and Self-Concept

Schizotypals reportedly do not tend to have strong emotions other than high neuroticism, anxiety, and fear5 1. They can have difficulty understanding other people’s emotions and difficulty expressing their own emotions, so they might have inappropriate or restricted affect (e.g., smiling when telling a sad story)5 1. Regarding their sense of self, there is often poor self-awareness, low self-esteem, and sensitivity to criticism, as well as feelings of inadequacy and insecurity5 1. Millon noted this dynamic may be an “abandonment of self.2 6”

👥 Social

Socially, they are often loners who are frightened of others5 2. One case example likened the “experience of social interaction as being similar to the feeling one has when one’s ‘knuckles accidently scrape across a carrot grater’.”1 OUCH, right? When engaged with others, they may take an inappropriate amount of time to answer, mutter to themselves, then only provide short responses, ramblings, tangential speech, or bizarre speech, though they may be comfortable talking about “highly esoteric topics5 1.” This can result in underachieving in areas of school or work5 1.

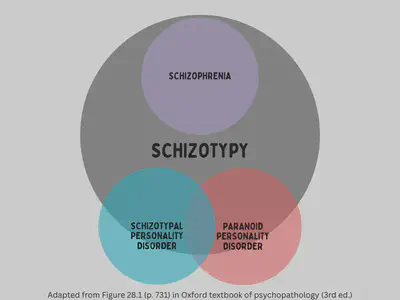

In conclusion, schizotypy is extremely complex and nuanced, while schizotypal personality disorder (according to the DSM) is only a small overlapping part of schizotypy. If you want help to better understand your own schizotypal-schizotypy-ness (or the dynamics of someone you care about), therapy and/or psychological testing can help! If you’re in Virginia (or a PsyPact state), check out Quest Psychological and Counseling Services for available services. If you’re a provider stuck on a case, Quest also offers consultations for mental health professionals!

References

-

Blaney, P. H., Krueger, R. F., Millon, T. (Eds.). (2014). Oxford textbook of psychopathology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality: Introducing a DSM / ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal (3rd edition). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Meehl, P. E. (1962). Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. American Psychologist, 17(12), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041029 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Meehl, P. E. (1990). Toward an integrated theory of schizotaxia, schizotypy, and schizophrenia. Journal of Personality Disorders, 4(1), 1–99. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1990.4.1.1 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR (5th edition, text revision.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Millon, T., Grossman, S., Millon, C., Meagher, S., & Ramnath, R. (2004). Personality disorders in modern life (2nd ed.). Wiley. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎