Schizoid Personality Disorder vs. Autism Spectrum Disorder

…Quiet…withdrawn…distanced from relationships…difficult to read…

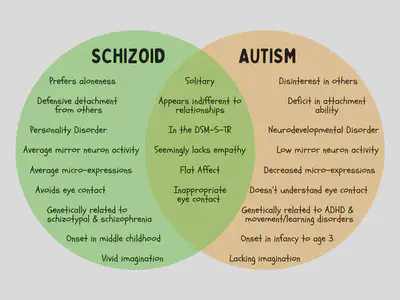

Those with schizoid personality disorder and those with autism spectrum disorder can look similar on the outside at first glance.

But beneath the surface, the two are very different! They have different roots, follow different paths, and carry different outcomes.

It can get pretty confusing, but let’s explore the similarities and differences between schizoid and autism!

Overlap Between Schizoid and Autism

Schizoid personality disorder and autism spectrum disorder overlap in their observable symptoms. Externally, others can see both those on the autism spectrum and those with schizoid personalities as lacking empathy, having odd communication, and preferring aloneness, as well as being sensitive, emotionally detached, socially disinterested, and cognitively rigid1 2. In fact, one study found a 26% overlap between Asperger’s disorder and schizoid personality disorder - the highest out of all the personality disorders1. However, both are not “allowed” to be diagnosed in the same person, per the DSM3.

The DSM-5-TR

In the DSM-5-TR3, criterion B of schizoid personality disorder specifically says that it “does not occur exclusively during the course of…autism spectrum disorder3.” Then it highlights there can be “great difficulty differentiating” those with schizoid from those with autism, especially if the symptoms are more mild, because both have “a seeming indifference to companionship with others3.” This is followed by one little sentence saying that “autism spectrum disorder may be differentiated by stereotyped behaviors and interests3.” …Not too much information here, so let’s look deeper.

Intertwined Terminology

A HUGE issue with understanding the difficulties between schizoid dynamics and the autism spectrum is the actual words that have been used to describe each concept. Schizo- (schiz-) means “split,” referring to the tendency of schizoid personalities to split off from the world and their own needs4. However, looking at the literature, schizoid personality disorder is lumped together with other disorders such as schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. In fact, literature often assesses schizoid phenomena on a spectrum of schizoid → schizotypy → schizophrenia. So there’s lots of confusing overlap between “schiz” words.

But to make it even more complicated, schizoid phenomena historically include the word “autistic” in describing a schizoid’s self-focused thought processes (autistic thinking), withdrawal into fantasy (autistic fantasy), and tendency to move away from others (autistic-contiguous position). Why? Well, because the actual word of autism in the dictionary comes from the Greek word “autós” which simply refers to the self. These terms have nothing at all to do with how we currently understand the word autism. To make it even harder, autism research has historically investigated low-functioning autism, high-functioning autism, and Asperger’s disorder, but we currently use the term autism spectrum disorder.

Genetics & Etiology

Before we get to genetics, it’s important to remember that schizoid is associated with schizophrenia in the research. We know that schizophrenia has a strong genetic loading with first degree relatives having an eight- to eleven-fold risk5. We also know that there is substantial heritability for autism spectrum disorder3. Yet, autism and schizophrenia do not show up in the same genetic lines2, which means they are genetically separate. Additionally, schizoid personality disorder has higher comorbidity with schizophrenic and dissociative syndromes, as well as other personality disorders such as, avoidant, schizotypal, and obsessive-compulsive syndromes6. In contrast, autism spectrum disorder has higher comorbidity with other neuro- and/or developmental diagnoses such as ADHD, movement disorders, learning/intellectual disorders, and epilepsy3. Put this all together, and there’s a clear delineation between schizoid as a personality style/disorder and autism spectrum as a neurodevelopmental condition.

Development

Because autism spectrum disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition, it most often presents early in childhood, around the age of 2 or 3, or possibly earlier2. (Of note, while it can present in later development or even adulthood, this is the exception and not the rule). Childhood is also where we see a lack of imaginative play and concrete thinking, as well as stereotyped behaviors3. For example, a child may not engage in social behaviors such as reciprocal eye contact, copying (social smile), or turn taking interactions (i.e. peekaboo, babble conversation). They might not engage in pretend play, only play with a specific toy constantly, and engage in repetitive body movements (i.e. toe walking, flapping hands, arching back, head banging).

Meanwhile, schizoid personality traits emerge around middle childhood2, which is approximately ages 6 to 11. In this stage, focus shifts away from primary attachments towards peers and social groups (i.e. classrooms, sports teams, friend groups). For example, a child might be observed to stare off into space daydreaming instead of engaging in a small group activity with peers. They can actually have difficulty figuring out make-believe from reality because of their strong imagination7. They may withdraw from social interaction and prefer solitary activities.

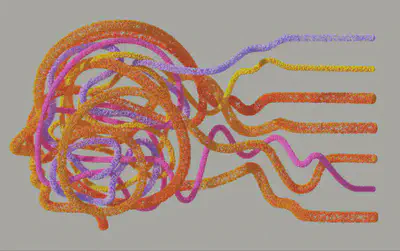

Mirror Neurons & Facial Expressions

I dug into some research about empathy, mirror neurons, and emotional expression and found something super duper fascinating! One study found that patients with schizophrenia indeed had deficits in observable facial expressions, BUT they had appropriate microexpressions8. So they have normal feelings, but don’t express them. They also found that: others who interacted with patients with schizophrenia decreased their own facial expressiveness and felt more negative experiences (which is perhaps why we overpathologize schizo- dynamics)8. Another study found that actively psychotic individuals had increased mirror neuron activity; schizophrenic individuals had average mirror neuron activity; and individuals on the autism spectrum were found to have little to no mirror neuron activity when observing others9. What this means is that those on the schizoid-schizophrenia spectrum don’t lack emotions and empathy at all, they’re just not expressive. In contrast, those on the autism spectrum have social hardwiring that is not intact. This matches with the research that proposes autism spectrum disorder involves more severe impairment and prognosis2.

In sum, we have a naming problem. We always have, and likely always will, since we can’t ever agree on things, and personality is way too complex to capture in labels, criteria, and boxes. But alas, we must do so to understand patterns. Along those same lines, the DSM is incomplete in its categorization, as with any theory. All research has limitations. But with the DSM, schizoid personality disorder is described using what is observable on the outside but not what’s inside. And that outside stuff overlaps with autism spectrum disorder symptoms, which is why we can’t just observe the shell! Schizoid and autism have different genetics, etiology, development, and internal processes.

If you want to better understand the differences between schizoid and autism, therapy and/or psychological testing can help! If you’re in Virginia (or PA, MD, DC for therapy only), check out our private practice, Quest Psychological and Counseling Services for available services. If you’re a provider stuck on a case, we also offer consultations for mental health professionals!

References

-

Lugnegård, T., Hallerbäck, M. U., & Gillberg, C. (2012). Personality disorders and autism spectrum disorders: What are the connections? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(4), 333-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.05.014 ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Wolff, S. (1998). Schizoid personality in childhood: The links with Asperger syndrome, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and elective mutism. In E. Schopler, G. B. Mesibov, & L. J. Kunce (Eds.), Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism? (pp. 123-142). Springer. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR (5th edition, text revision.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

McWilliams, N. (2011). Psychoanalytic diagnosis: Understanding personality structure in the clinical process (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. ↩︎

-

Lo, L. E., Kaur, R., Meiser, B., & Green, M. J. (2020). Risk of schizophrenia in relatives of individuals affected by schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 286(112852), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112 ↩︎

-

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality: Introducing a DSM / ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal (3rd edition). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ↩︎

-

Mittel, V. A., Kalus, O., Bernstein, D. P., & Siever, L. J. (2007). Schizoid personality disorder. In W. O’Donohue, K. A. Fowler, & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), Personality disorders: Toward the DSM-V. (pp. 63-79). Sage. ↩︎

-

Kring, A. M., & Moran, E. K. (2008). Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: Insights from affective science. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(5), 819-834. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

McCormick, L. M., Brumm, M. C., Beadle, J. N., Paradiso, S., Yamada, T., & Andreasen, N. (2012). Mirror neuron function, psychosis, and empathy in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Research: Neuroimaging, 201, 233-239. ↩︎